- Home

- Annie Ali Khan

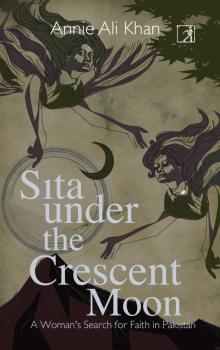

Sita Under the Crescent Moon

Sita Under the Crescent Moon Read online

SITA

UNDER THE CRESCENT MOON

A Woman’s Search for Faith in Pakistan

ANNIE ALI KHAN

A special thank you to Manan Ahmed Asif for showing me the way of the satiyan.

Dedicated to Qurratulain Hyder

I bow down before the mosque of the great Pir at Naupara And the mosque of Hirmai to the left For the great saint once passed through these tracts Now I proceed onwards and arrive at Sita Ghat Where I worshipfully bow before the ideal of womanly virtues, Sita Devi

— River of Fire, Qurratulain Hyder

[After partition] The Muslims created a Pir, the same way Hindus created a Devi or a Devta for everything. There is a Pir for raag, a Pir for clay utensils, a Pir for pingoray. All of Sindh became the land of Pirs. Even when the jogis chanting the mantars for the sacred naag, became Muslim, they still belonged to the tribe of Shiv and followed Gorakhnath. Similarly, the Hindus began to consider Ramzan the month to purify and offered taweez and nazar during the month of fasting

— Translated from Sita Haran, Qurratulain Hyder

In my childhood, we used to go to the mandir. There were countless Shivalay in Tando Adam, known as the Kashi of the province of Sindh. In HeemKot, there is a mandir of Maha Dev. I went there once with my aunt. I used to visit the mandir at Clifton beach in Karachi, for Shivratri with my mother. My grandmother was a follower of Kali. There is a roop of Kali we call ‘Thar-mai’ meaning the Devi of the Thar desert

— Translated from Sita Haran, Qurratulain Hyder

All is momentary, all is pain. Sarvam Dukham

— River of Fire, Qurratulain Hyder

FOREWORD

At Hub Chowki, a historic-city-turned-transit-town is now the gateway between Sindh and Balochistan. Those travelling through are greeted by a road sign that reads ‘Mundra’—a Sanskrit word meaning temple or place of worship or chasm— overshadowed by a larger sign with a new name, proclaiming, in bold Arabic script, ‘Seerat’, meaning inner beauty, heavenly light hidden from view, veiled. These are the many paths to the sacred and the beautiful that abound in the Islamic Republic of Pakistan. May the goddess protect us.

I was on my way from the city of Karachi, once a humble fishing hamlet and now the seventh largest city in the world, to the elusive temple of the Goddess Durga at Hinglaj. The temple was nestled in the heart of a lush oasis halfway along the barren coastal belt of Balochistan: Pakistan’s largest province by land mass, but with the smallest population. I rode through an endless expanse of sky, sea and sand broken by brooding dark mountains, humble fishing hamlets and ancient Baboor trees, their sinewy branches looking like sadhus in repose and an occasional camel trotting by past the road that led to Hinglaj. The temple mountain, located in one of the most remote places in the world, was the resting place of the devi the locals called their Nani Pir, or great mother saint.

In 2016, I returned to Karachi, the city where I was born, after seven years of living in New York. I used to work as a model in Karachi, I came back to it as a writer. The cityscape of the southern port area had changed even as much as it remained the same. The skyline was filling up with tall towers, glinting silver under a scorching sun. We used to frequent the main seacoast area as children, riding camels and eating candy floss. On one occasion my mother had taken us—stuffed all the children of the family, siblings and cousins both, into her car and drove us through heavy rain to see the approaching cyclone that never arrived. This area was now barricaded by a gateway with an entry fee.

The province of Balochistan was the darkest corner of the country. My grandfather Sheikh Abbas had travelled there regularly in his open jeep, conducting land surveys for a development project in Hub, when he was working as a civil engineer in the nineties. Now, as I crossed the two rivers named Lyari and Hub, both of which flowed into the Arabian Sea dividing the provinces, a full-fledged uprising was underway in Balochistan. The Sarmachaar—a Balochi word meaning men with their head held in the palm of their hand, crying for freedom of the land and in revolt—were in battle with the state. This war went back to the very inception of Pakistan. With its legacy of dictatorships, the state responded to each insurgency since 1947 with the iron-fisted might of the military, silencing voices of dissent in and around this land rich in resources and peopled by the poor.

Hinglaj, in the heart of the province, is as sacred as it is remote. The ancient temple is located along an endless terrain following a coastal route that reaches beyond the Malabar region in south India and extends further up north, past Rajasthan, then the coastal cities of Iran. I read somewhere that the road between the sea-facing shrine of Abdullah Shah Ghazi in the port city of Karachi and the shrine of Haji Ali, half submerged in the sea in Bombay, was once a route well-travelled by pilgrims of the Sufi order—before the borders got in the way. These pathways of dust, ancient routes of pilgrimage rising off naked feet, are dotted by graves, some of them marked by tinselled red and green cloth, others disappearing into the earth; testament to the centuries of pilgrims who made their way to Nani Pir in Hinglaj.

Durga, born to King Daksha as Sati, says the Mahabharata, observed strict penance, making sacrifice of body and soul to attain Shiv as her husband. At Daksha’s yagna, a ritual ceremony, priests sat around a sacred fire performing sacred rites. All the deities of the heavens were invited to Daksha’s yagna except Shiv and Sati. Uninvited, Sati made an appearance, and was insulted by her father. Her sisters were far more distinguished and worthy of honour than she was, Daksha said. Sati, looked towards the gathering, ‘My husband Shiv, the lord of lords has been insulted for no good reason,’ she said. ‘The scriptures say those who steal knowledge, those who betray a teacher and those who insult the lord are great sinners.’ Durga then flung herself into the flames of the ceremonial fire, the sacred yagna turned into the means for a sacrificial pyre.

Learning of the death of his wife, Shiv, in a state of fury, took a strand of his hair and turned it into a fearsome creature that beheaded Daksha. Yet, the yagna had to be completed; Daksha was restored with a goat’s head. But Sati’s soul could not be brought back. In despair, Shiv, carrying Sati’s body in his arms, standing above the universe, began a dance of destruction. To save the heavens, Lord Vishnu sent forth one of his powerful chakras that hacked at Sati’s body; taking Sati away from Shiv, breaking his hold over—and his attachment to—his beloved. The pieces of her body, fifty-two in all, fell to the earth. The places where each part landed became sacred temples of worship. Durga’s anklet and neck fell in the valley of Kashmir. The head landed on a remote mountain in the heart of Balochistan; that most dangerous of provinces, in a country perpetually at war, too became the site of remembrance for a woman’s sacrifice.

I left Karachi on the morning of the ninth day of Moharram, a big night in the commemoration of another narrative of a family torn apart and dismembered. These were the events of Karbala, when family members of the Prophet Mohammad—his grandson Hussain in company of mostly women and children—were killed on the battlefield. He had dared to lay claim to political leadership and the ruling polity surrounded him with a massive army, and without the mercy of a single drop of water, took their innocent lives. During Ashura, the first ten days of the month of Moharram, millions of Muslims remember and mourn the sacrifice of those who refused to bow to injustice. I left behind a Karachi under curfew, blocked by shipping containers to keep in check the thousands of mourners flowing through the centre of the city. Rallies full of the grieving, who were remembering the bloodshed of innocents and inflicting fresh wounds on their bodies, their blood flowing afresh on the streets: a Moharram relived.

It was truth I sought as I made my passage into Balochistan, armed with a

notebook, camera and an audio recorder, with a vague outline of a story in my head. I was accompanying a family of yatris on a pilgrimage to the temple, entering the heavily patrolled and policed borders of the province with them. It was also the last night of Navratri, the festival celebrating the victory in battle of the goddess Durga over a demon buffalo to restore dharma, the order of the cosmos. Sati’s suffering and sacrifice and the joy of her victory were remembered like Moharram, like mohabbat; love in the heart, eternal and ever-flowing like the suffering that was life on earth.

Sati was a woman celebrated as a goddess after she was immolated. Her sacrifice, like the sacrifice of Karbala, was a reminder: nothing came without a price in this world. Like the shaheed lays down his life in struggle, the sati burned for a greater truth. Where the word ‘shaheed’, in Arabic, is one who proclaims or one who witnesses the truth, the word ‘sati’, in Sanskrit, means ‘real, true, good or virtuous’. Sati, the woman, burned on her husband’s funeral pyre.

Sati was also alive—the Hinglaj Mata I met in Balochistan.

The local legend surrounding Nani Pir was that the great mother saint taught a lesson to an evil king, Hinglaj, notorious for raping the women of his own kingdom. Durga is said to have roamed the gardens of the king’s palace in the roop of a beautiful woman until the king, in pursuit, followed her into the wilderness, where she transformed into a terrifying deity. The king, realizing his folly, begged forgiveness and promised to serve the Mata. Durga granted him pardon and turned into a stone murti, revered to this day by people near and far looking to the great mother for justice.

My grandfather was born in the northern city of Shikarpur, once the commercial hub of Sindh before the enterprise shifted to Hyderabad, leaving Shikarpur to turn into a dusty backlot. He first went to Bombay, where he completed his Bachelor’s, and then to the United States to pursue a Master’s in engineering. There he married an American woman, before moving back to Pakistan. He settled in Karachi, divorced the American woman and married my grandmother. I never asked my grandfather why he kept statues of Durga on his study table. Just as I never asked him why he had a photograph of the Ka’bah on the wall across the bookshelf.

Times were changing around my grandfather. Sindh had seen little or none of the religious or communal violence experienced in the province of Punjab in 1947. But over the years, and after a decade of General Zia’s Islamist dictatorship, a dark era of curfewed nights and religiously driven ideas of identity swallowed Sindh. Hindus had largely left in the 1940s. Those too poor to leave melded into the landscape, hoping to not be noticed. Still, conflict over god continued. The fifties were attacks on Ahmadis, the eighties and nineties were attacks on Shias. Anti-Shia riots were commonplace in my childhood. I remember one time in the early nineties when my cousin had come to spend the weekend at our house. By the following week he was unable to go home as the streets were closed, due to clashes between Shia and Sunni groups. My brother and I were happy to get a day off from school but soon, staying inside, feeling trapped, we began to think of ways of getting my cousin home safe. My cousin said, if approached and asked whether he was Sunni or Shia, he would reply with the safest answer and say he was a bhakt of Kali. He then proceeded to do a comic rendition of Bharatnatyam.

My cousin never failed to try and convert to Islam the local video wallah in his neighbourhood, a Hindu fellow from whom his mother, my aunt, rented all the pirated Bollywood films. To hear him call on Kali was both funny and a reminder that in many ways, we were children trying to cope with what were utterly confusing times. Everything we knew was turned upside down. Everything we were was questioned and re-fashioned to fit a changed landscape. I remember my math professor in college in Karachi calling me to his office to inquire if I was Shia, since Quratulain, he said, was a Shia name. I wondered what math had to do with my religion. But I did not say anything.

We were encouraged to discuss the religion at the centre of the country’s politics. I remember the time a neighbour invited a maulana to her home and had the children gather around to ask questions. I asked the maulana what was at the end of the universe and what was beyond that which lay there. The host took me aside and said such questions were likely to lead me astray from my faith. The gathering ended soon.

Meeting Durga at Hinglaj reminded me of the sacrifices life demands at every step. I began to follow the satiyan, the seven sacred sisters, travelling, all through Sindh and Balochistan. The search for the elusive sati became a quest to learn more about the legend of women burned or buried and then worshipped. I decided to make a pilgrimage for the seven women worshipped after being set on fire or swallowed alive by the earth. Parveen Naz, a social worker, accompanied me for part of the journey that took me across the length and breadth of Sindh and a few remote spots in Karachi.

THE ROAD TO DURGA

‘Arre Allah.’ My grandfather’s face was anguished, his thick white eyebrows were raised. He was looking at the tiny statuette of the goddess Durga. ‘My god, Annie, what have you done?’

I had no answer, but even as a seven-year-old I knew I had done something terribly wrong.

Every year, my grandparents used to take us to Uncle Devraj’s house in Karachi, where together we celebrated the new moon sighting for Diwali. Devraj was Hindu, and my grandfather was Muslim, but they both spoke Sindhi and shared familial roots. Theirs was not a unique story. Unlike in Punjab, where Partition brought bloodshed on an unprecedented scale, the Sindh province to the south saw little or no communal violence. The Hindus of Sindh largely stayed behind. Muslim and Hindu families shared bonds and cultural values that reached back generations; a sense of respect for community prevailed. My grandfather even had his own collection of the Devi goddess in his study, one which he revered. I often saw him offering his namaaz at his chair under the gaze of Durga. Perhaps I’d taken the Durga from Devraj’s house thinking it would be equally at home at ours.

But over the years, things slowly began to change. General Muhamad Zia-ul-Haq, who served as president from 1978 until his death in 1988, instituted an era of Islamization that was defined by militants and increasing violence. A series of targeted attacks began on religious minorities. Hindus, Sikhs, Shia Muslims, and Ahmadis, members of another sect that is considered non-Muslim in Pakistan, became prime targets. Throughout the 1990s, newspapers regularly carried stories of sectarian violence. After Devraj’s death, his family decided to move to Bombay. They came to see my grandmother one last time before leaving.

‘Things are not the same anymore,’ his wife told my grandmother. After my grandfather’s death, none of his children claimed the Hindu figures he kept in his office. My grandmother gave away the statues from the shelf in his study to an antiques dealer.

Those memories, long forgotten, came flooding back when I decided to make a trip to the Hinglaj, the holy site located half a day’s journey from Karachi, in the troubled neighbouring province of Balochistan. Since Partition, Balochistan has seen a number of insurrections, each cry for a free state bringing a brutal response from the ruling state in the form of military reprisals. The province makes up a major portion of Pakistan’s coastal belt and has vast natural resources. Yet it remains the poorest province in the country. In recent decades, it has also become a centre of Islamic militancy. When I learned that a revered Hindu site was located there, it came as a surprise. It seems that borders and political unrest have done little to dissuade pilgrims from both Pakistan and India from tracing an ancient pathway to the resting place of the goddess Durga.

My grandfather never spoke of his friend as a Hindu. As a Muslim he too revered Durga. Her devotees range along the entire coastal belt—now divided along lines into Sri Lanka, Tamil Nadu, Maharashtra, Gujarat, Sindh, Balochistan. To try and label and define the Hinglaj in the current narrative—as Hindu or Muslim—is to employ the tools used by invaders and rulers, those in power. The people’s history of Hinglaj was in the sands of the coastal lands, traversed for hundreds of years by pilgrims searching for

truth, who continue to flock to the caves drawn by a powerful story that survived centuries of inqilaab, upheavals traced in the dust lifting off the feet of a pilgrim.

Roads and highways and political and security borders notwithstanding—in making their way to the Hinglaj, the pilgrims defied artificial divisions. It was this pathway I now sought to follow. The path leads to a temple located in a cave in the Hingol Mountains. This was the spot where the goddess Sati’s head is said to have fallen from the sky after her body was cut into fifty-one pieces by Vishnu. ‘The Hinglaj is to us as the Ka’bah is to you,’ said Danesh Kumar, who had offered to accompany me here, referring to the shrine in Mecca toward which all Muslims direct their daily prayers.

Kumar was a local politician and a member of the representative committee of the Hinglaj temple. Clad in a white shalwar kamiz, he fit the bill of both reverent pilgrim and veteran politician. A journalist friend had introduced me to Kumar, who was on his way to pay his respects at Hinglaj and had offered to be my guide.

We were in Kumar’s Hilux—a massive, Japanese-made silver truck. Kumar and his family hailed from Las Bela, which the locals referred to as Laasi. The district was spread over the area from the southern town of Hub, stretching halfway across the Makran belt overlooking the Arabian Sea. Kumar had lived in Laasi until a few years ago, when he moved to the port city of Karachi for the sake of his son’s education. His son, Vansh Kumar, a precocious ten-year-old, sat patiently on the backseat playing a game on his tablet. ‘People go to Hingol for vacation, but they should try and learn a little about its history,’ Vansh said.

Inside the Hilux, we moved comfortably along the highway leading out of Karachi. With one hand on the steering wheel, Kumar called the private car tracking company where his vehicle was registered, informing them he was soon going to cross into Balochistan. After placing the call, Kumar remembered that this was the first time I was travelling to the province, a fact I had mentioned to him over the phone. He turned to me in the rearview mirror. ‘People are very afraid to go into Balochistan,’ he said. ‘You are very brave to go, which is why I decided to take you there myself.’

Sita Under the Crescent Moon

Sita Under the Crescent Moon